MAISON JAOUL

The Maisons Jaoul are two, almost identical, villas built be Le Corbusier after the war, showing the evolution of his views on the design of individual houses. The twin villas are situated in the upscale Parisian suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine and were built for M. André Jaoul and his eldest son. The general design dates way back to 1937, with it taking its final form reportedly in 1951 and construction being completed between 1955 or 1956, according to different sources(1). The maisons Jaoul can be understood as the real turning point for the practice of the man with the round glasses, after his gradual, post-villa Savoye drift away from the devotion to his own 5 points for a new architecture.

None of Le Corbusier's 5 points is decisive for the design of the project, and all other trademark elements of the 1920's villas are nowhere to be found. With the abstract, homogenous, vocabulary of the 20's long gone, and with a new perspective from his travels and the hybrid tryouts of the 30's, the architect has now the occasion to work on the basis of an evolved language, closer to the linguistics of materials, structure and tectonics. Brick, concrete and wood participate in a hierarchy of tectonics and grids that are worlds apart from the white abstraction of extra-thin wall and wide window present in the 20's. The toit-terrasse gives way to the Catalan vault, going back to a fundamental, almost primitive, concavity. This construction system also sounds the end of the plan libre, with the imposed hierarchy of load-bearing longitudinal walls. Without columns, the façade libre and the horizontal windows are replaced with an almost mysterious heterogeneity of concrete, brick, stone and glass. Last but not least, the pilotis gives way to a closed plinth, which is tucked into the terrain instead of glorifying the dwelling's detachment from it.

The maisons Jaoul are in a way the closed door behind Le Corbusier, marking his definite passage from perfect construction to an intangible notion of perfection and in that, a transition, from the homogenous conceptual premises of ''new architecture'' to the heterogeneous paradigm of ''inexpressible space''. This four-dimensional geometry of ''architecture, painting, sculpture and space''(2), first put into words in an article in ''L'architecture d'aujourd'hui'' in 1946, had one, invisible parameter holding it all together; the Modulor. Under the ruling modularity of the nombre d'or, Le Corbusier allows concavities to contain convexity (as in the relation of the whole scheme of the houses to punctual fluidity created through open strips in the heavy walls), and works on the rotated almost-repetition of the two volumes (with the original grid of the wood/glass window panels inserted into the uneven, load-bearing, brick wall). These two exercises are just two examples of how the spatial universe of the villas is a very eloquent example of the space that is ''precise, just, sounding and consonant''(3), undulating like irregular vibrations of the modulor, announced in the text of 1946.

Heterogeneous Image

The central axis of the drawn research on Jaoul, is the visible intention to forward a clear image of heterogeneity, as a counterpart to the intensive ‘’marketing’’ of the’’ new architecture’’ back in the 1920’s. Although Le Corbusier’s late works do not follow the same manifesto-centered approach as his early ones, in maisons Jaoul there is a clear intention to demonstrate the new process of inexpressible space and not merely experiment with it. Within this observation, the analytical drawings are focused mainly on the extroversion in this ambiguous approach and thus the exterior spaces and perception of the houses as well as the rules and phenomena at work in the facades.

Already in the study of the general writing of the plan (figure 1) an array of operations indicate a research of heteronymous spatiality. The complex is generated on the basis of a typical volume, that is then rotated ninety degrees and subsequently mirrored. The two almost identical houses that occur through this operation, form the poché of a central terrace by which they are accessed, truncating its ideal square form in the two angles. The center for the initial rotation becomes an important stage in the procession of the observer towards the houses, which happens by means of a ramp, connecting the elevated terrace with the level of the terrain. The form and position of the ramp is not irrelevant to the above; it is the consequence of another rotation of the typical volume, according to a shifted center of rotation and a slightly smaller radius.

This initial geometric heterogeneity in plan, further unfolds in a more specific way in the study of the central terrace of the complex (figure 2). This form stems from an initial square, invaded by the two volumes of the houses, which breaks its ideal clarity and dominate its spatial premises with their interaction, to create a typically concave space(4). On top of this feature, the perceptive progression from ramp to terrace to house follows a pattern where all facades are seen under oblique angles rather than frontal view (figure 3), a fact that underlines from the start the complex spatial hierarchy and the ambiguous image that is intended.

Details of the Inexpressible Space

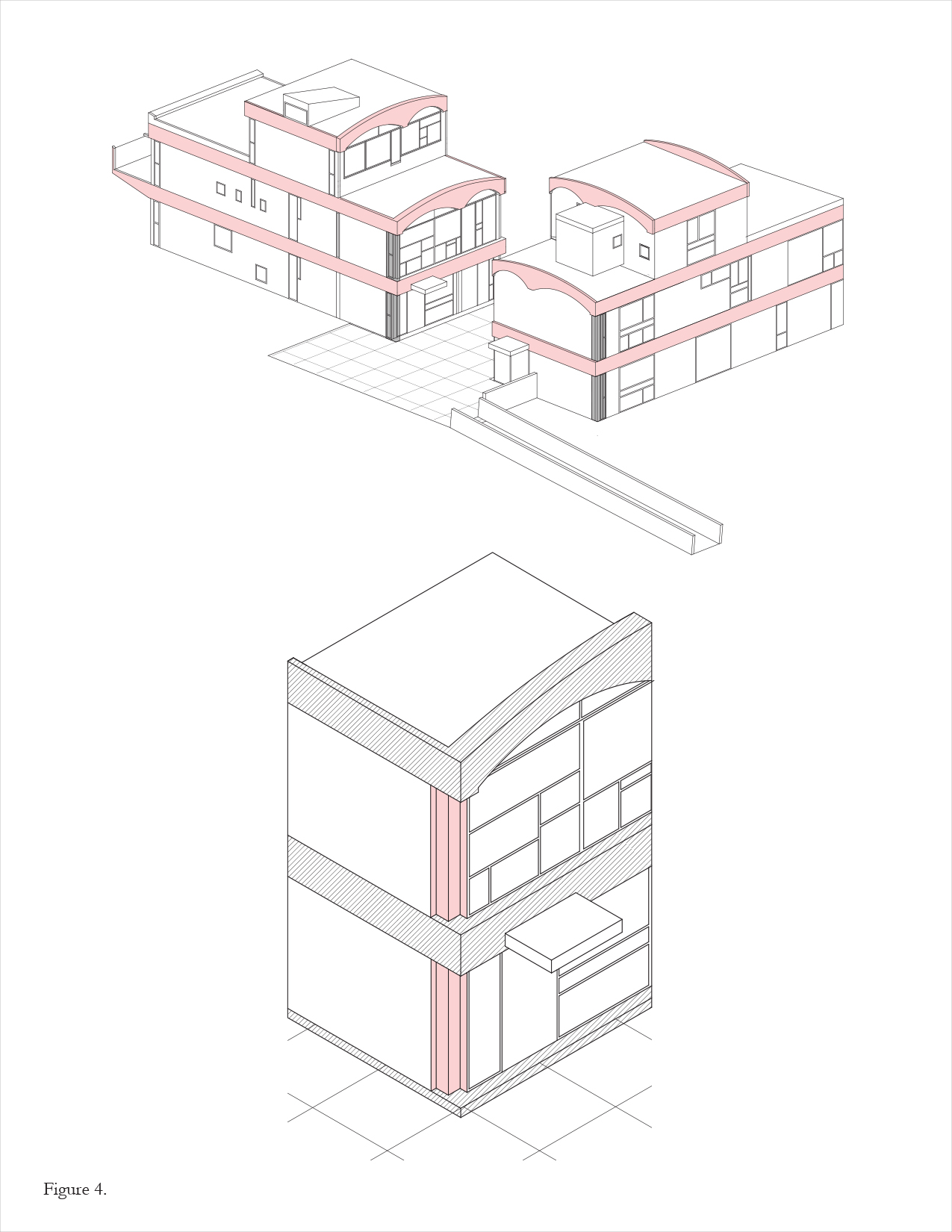

More in detail, we can choose from a generous multitude of elements that indicate clearly the maisons Jaoul’s heterogeneous identity. A first point where this fact is visible, concerns the work in the facades, in the organization of the relation between the horizontal elements, dominated by the form of the catalan vault, and the vertical surfaces of the walls and windows. Le Corbusier’s way of dealing with the angle of the building is very telling in that respect (figure 4). This choice of configuration is already at work in the general relation between the continuous trace of the horizontal separations and the fragmented sequence of brick walls and irregularly subdivided windows. However, it is the vertical connection between the perpendicular facades, which is sinuous and sunken into the poché of the continuous vertical surfaces, that creates an effect of chiaro-scuro and thus puts forth the predominance of the horizontal geometry created by the vaults. Indeed, this works in the sense of the overall heterogeneity, as the combination of the rounded forms of the vaults creates an intricate and somewhat outlandish contour that is the most characteristic element of the external expression.

Even though this expressiveness of the vaults is valued and used to benefit the overall heterogeneous expression, this element is itself submitted to the process of fragmented writing and differentiation that it serves. In fact, although the higher floors display their vaulted ceilings, the ground floor is chosen to feature a simple concrete slab that is expressed in the same way on the façade (figure 5); in a very simple manner, a reading of identical repetition is avoided. Moreover, the same effort is made with regard to the pattern of the window panels. Although all stemming from a modular system, the measurements in the subdivision of the glass are differentiated as much as possible between the panels of a given façade, something which is demonstrated with the superposition of their shapes (figure 5). Through this exercise, we observe that the only frequent convergence occurs with horizontal elements, as if they were a fragmented echo of the horizontal lines of bare concrete.

The writing of the slabs and windows deserves yet another viewpoint, as it is absolutely central in the affirmation of heterogeneous principles that Le Corbusier attempts in the maisons Jaoul. The examination of horizontal and vertical alignments that transcend the compositional tools that shape the façade -concrete lines, brick walls, glazed panels-, reveals an opposite rule between the two dimensions (figure 6). All vertical lines that are chosen to be materialized are distributed between a vast array of axis, with rarely more than two vertical lines aligned. In the horizontal dimension, aligned elements are more frequent, in an effort of diversion of practical constraints to the benefit of the differentiated rules of the whole.

For the last act of this analysis, we need to look at the relation of exterior to interior in the houses (figure7), which provides one more example of the new premise in Le Corbusier’s architecture. The floor plan is characterized by punctual clarity, with the presence of the stairs as a repeated layer, perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the houses, or in the rather clear organization of interiors into long strips. This seemingly clear logic is subject to a similar process as most of the aforementioned elements and events, especially in its communication with the exterior. The subdivision in elevation is, more often than not, geometrically irrelevant to the organization of interior space. From our viewpoint focused on the affirmed image of this process, this disconnects the expressive qualities of the facades with the building’s interior, introducing another layer of fragmented writing. Seen outwards from within, as observed by James Stirling, this choice blurs the limits of the spaces and makes impossible any clear perspective or understanding (5).

Romantism of the “mal foutu” (messed-up)

These examples are only parts of the demonstration in heterogeneity that Le Corbusier offers us with the maisons Jaoul. They were chosen to prove just that; In Jaoul, we are facing a real demonstration, a kind of silent manifesto, rather than an experiment or an exception. This is supported by the record of Le Corbusier's own discourse at that time. Only a few years later, he called his late approach a ''romantism of the messed-up'' -romantisme du mal foutu-, thereby affirming explicitly his theoretical evolution towards heterogeneity and a larger notion of ambiguity, that was chosen as the subject of this research.

Up to this point the genealogy of heterogenous space hasn't been the subject of explicit reflection in this article. It was deliberately used in a very straightforward way, with a slight, implicit, adapatation to the maisons Jaoul operated along the way. Through the examination of this project from the point of view of intended heterogenous writing, the agenda was to bring to light a fragment of the ambiguous evolution of this notion.

To formulate a meaningful conclusion, it is necessary to take a look back to the historical aspect of the events involved and the way in which the information harvested relates with issues of the architectural discipline today. Since Gian Battista Alberti, and up to the current parametric/digital interpretation of the matter, it seems that heterogeneity has been above all a means of contestation in the aftermath of clear and affirmed shifts. The case of Le Corbusier is particularly symptomatic in this respect, in the sense that he contributed himself to the shift in question and uses this means to contradict his own past postulates. The study of Jaoul can thus be related to the blurry contours of the somewhat cyclical reappearance of heterogenous writing as a radical means to move forward from major ''shocks'' in architectural history.

Selected Bibliography:

Boesiger, Willy. Le Corbusier – Oeuvre Complete, Vol. 5. Basel: Birkhäuse r, 1995

Le Corbusier. L'Espace Indicible. In:''L'architecture d'aujourd'hui'', special edition: ''Art''. April 1946

Le Corbusier. Vers une architecture. Paris: Flammarion, 1995.

Eisenman, Peter. Ten Canonical Buildings: 1950-2000. New York: Rizzoli, 2008.

Eisenman, Peter. The Formal Basis of Modern Architecture : Dissertation 1963, Facsimile. Baden: Lars Müller Publishers, 2006.

Frampton, Kenneth. Le Corbusier: architect of the twentieth century. New York: H. N. Abrams, 2002.

Lucan, Jacques. Composition, non-composition. Translation by Theo Hakola. Lausanne: EPFL Press, 2012

Lucan, Jacques. “Nécessités de la clôture ou la vision sédentaire de I'architecture” in Matières 3. Lausanne: EPFL Press, 1999.

Maniaque Benton, Caroline. Le Corbusier et les maisons Jaoul – Projets et fabrique. Paris: Editions Picard, 2005

Maniaque Benton, Caroline. Le Corbusier and the Maisons Jaoul. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009

Stirling, James. Garches to Jaoul - Le Corbusier as Domestic Architect in 1927 and 1954. In: The Architectural Review n° 705. September 1955

(1) Caroline Maniaque, Le Corbusier et les Maisons Jaoul - Projets et fabrique, Paris: Edition Picard, 2005.

(2) Le Corbusier, L’Espace indicible (inexpressible space), in the magazine ''L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui'', special edition “ Art ”, Paris: 1946.

(3) In the original text: ''Précis, juste, sonnant et consonant'', Ibid.

(4) “The existence of a building, absolutely isolated, can only be left to architecture; the moment that two buildings are present, a relationship is established, a grouping emerges…Relationship and assemblage signify rapprochement, possibilities of proximities and contiguities: they lead to the constitution of a concave space.” Jacques Lucan, “Nécessités de la clôture ou la vision sédentaire de I'architecture” in Matières no. 3, Lausanne: EPFL Press, 1999.

(5) In the Jaoul Houses, “there is certainly no question of being able to stand inside and comprehend the limits of the house” James Stirling quoted in Caroline Maniaque Benton Le Corbusier and the Maisons Jaoul, New York, Princeton Architectural Press, 2009