SRO | Rethinking Domestic Space in San Francisco

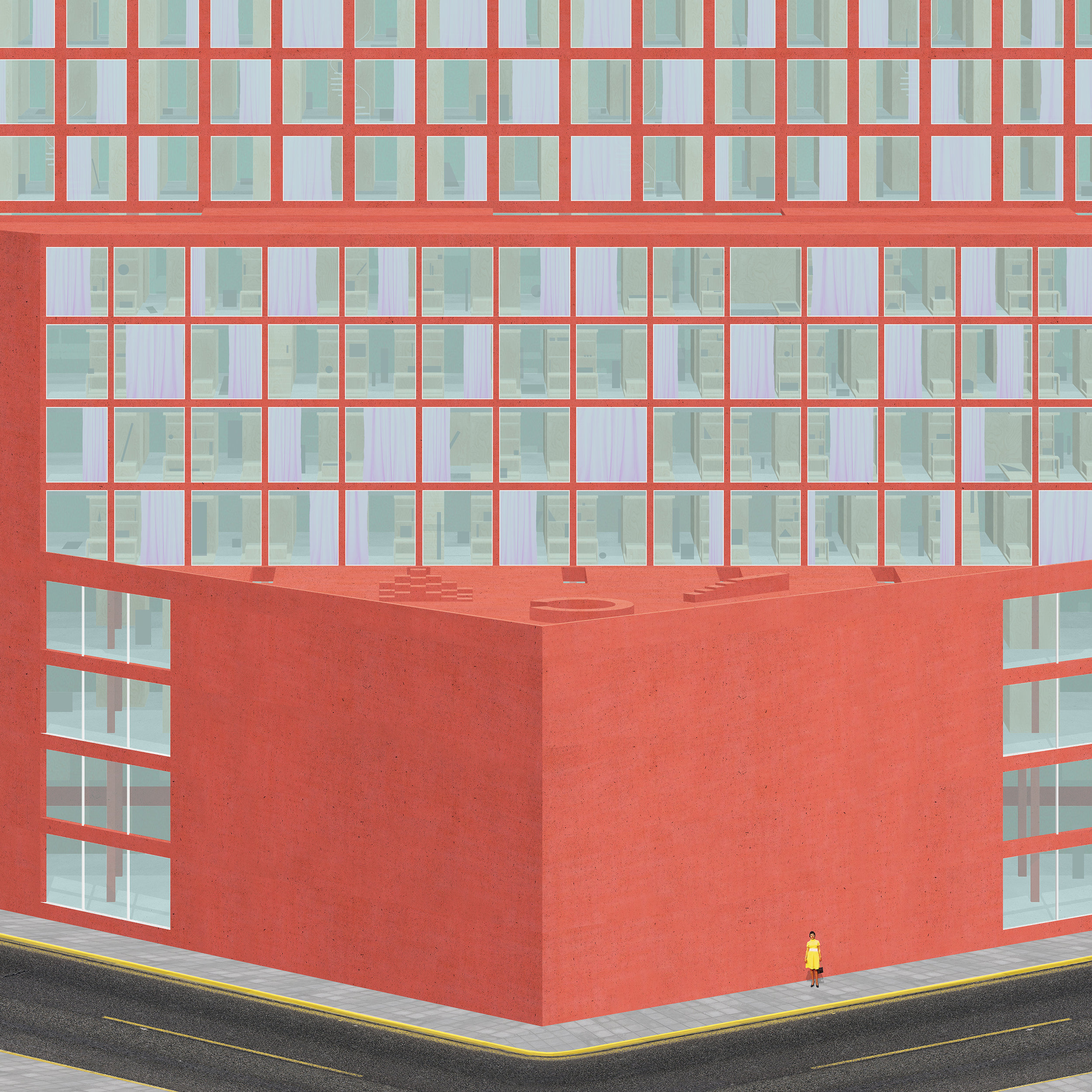

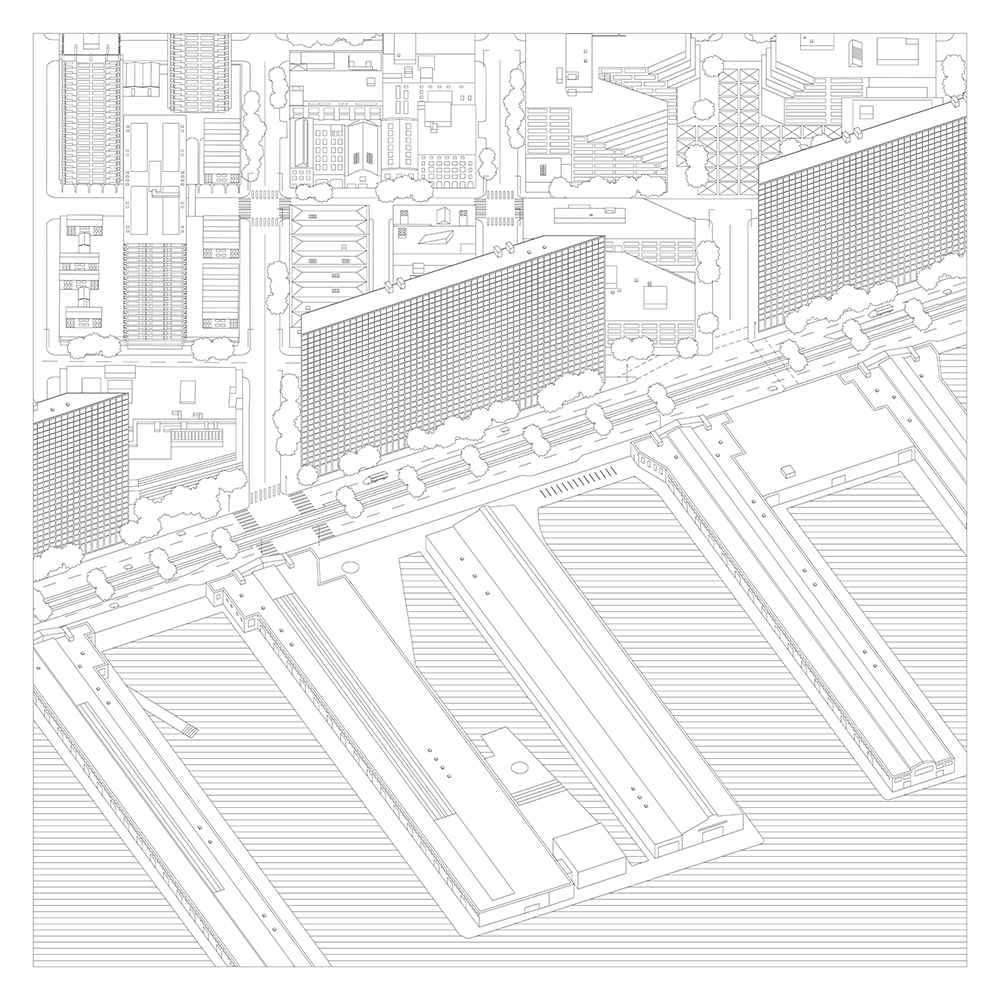

Our project proposes 6000 units in eight residential towers facing the waterfront along the Embarcadero, creating an urban edge to the city as well as attempting to recoup the housing stock extirpated by the closing of residential hotels and SRO’s in San Francisco. Americans have lived in residential hotels for over two hundred years. From the 19th century boarding house to the residential hotel, people have chosen to live communally. Residential hotels and particularly Single Room Occupancy (SRO) hotels are deeply rooted in San Francisco’s history, but have unfortunately suffered from the misrepresented idea that these were places of blight and crime, eventually leading to the pandemic demolition of thousands of units. In 1980, permanent hotel residents in San Francisco outnumbered public housing residents three to one.(1)

However, today San Francisco has one of the most aggressive regulations for their preservation in the United States, unlike New York where the construction of SROs is strictly forbidden by law. Contemporary depictions of such spaces only perpetuate the fallacious rhetoric espoused by the states and municipalities. Believing in this contemporary misrepresentation of the SRO is forgetting a vast chapter of the residential hotel’s history, which once ranged from the high end palaces and club such as the Ritz Tower, Plaza Hotel and the University Club in NY or the Tubbs Hotel in Oakland to well-functioning, middle class SROs in the city. Although the SRO often lacked extensive communal facilities, the typology nonetheless serves as an important model for housing those in precarious working and living situations. Unfortunately, the images today associated with the SRO, depicting spaces of impoverishment and degeneracy primarily inhabited by vagrants and addicts, belie the extensive history of the residential hotel as home to a wide array of socio-economic classes. Such spaces, particularly residential hotels, proved to be especially suitable for those living outside of the traditional structure of the nuclear family, fostering sociality through shared facilities and communal activities. In some cases, this lead to the eventual freeing of young working women from the burden of domestic labor. Yet these great bene ts was perverted to support the myth that such spaces inevitably become breeding grounds for immoral and licentious behavior. Thus the invention of the SRO as a public nuisance emerges primarily from the desire to preserve the family unit and the individual household as a fundamental means of governmental control, not necessarily from concrete or valid evidence in support of such a characterization.

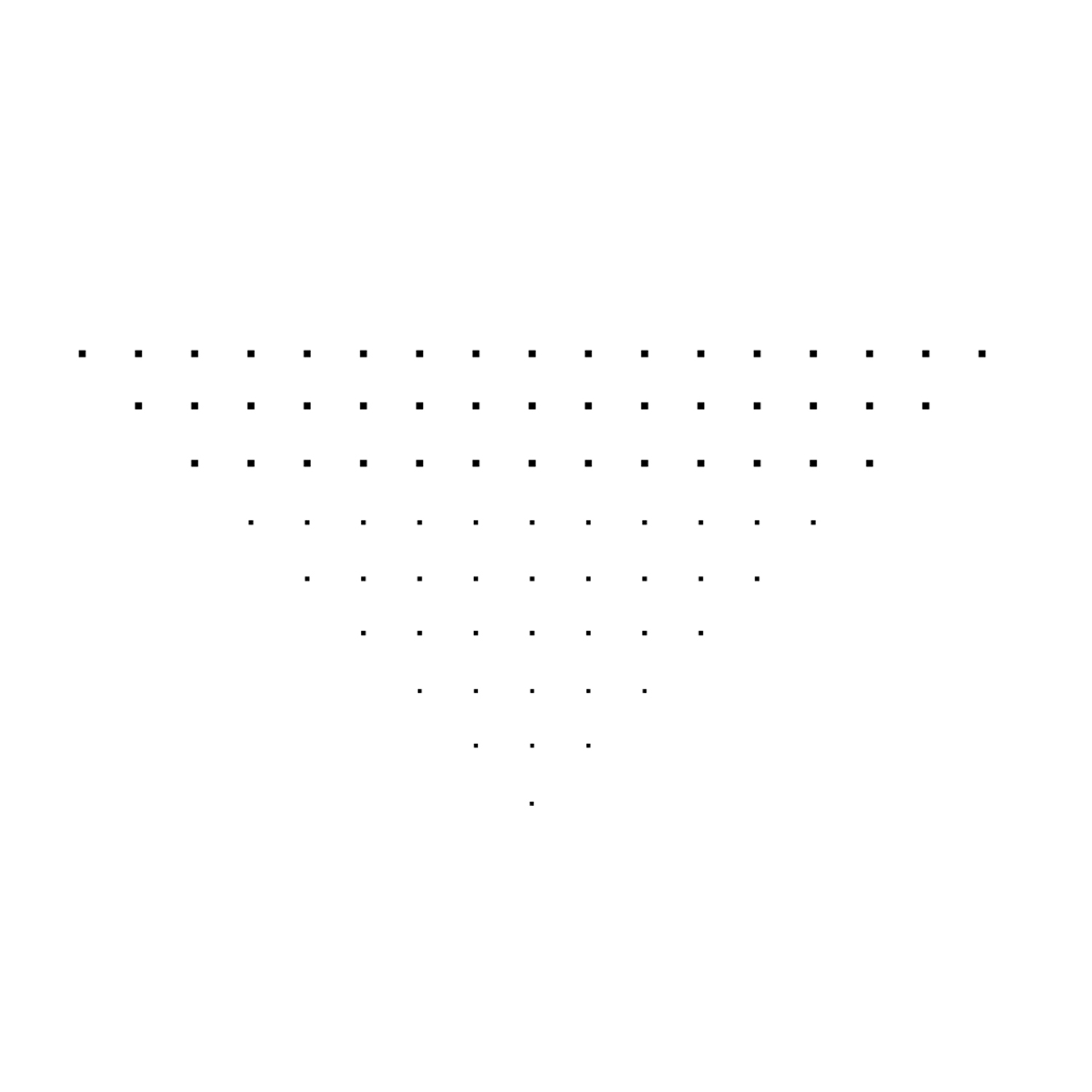

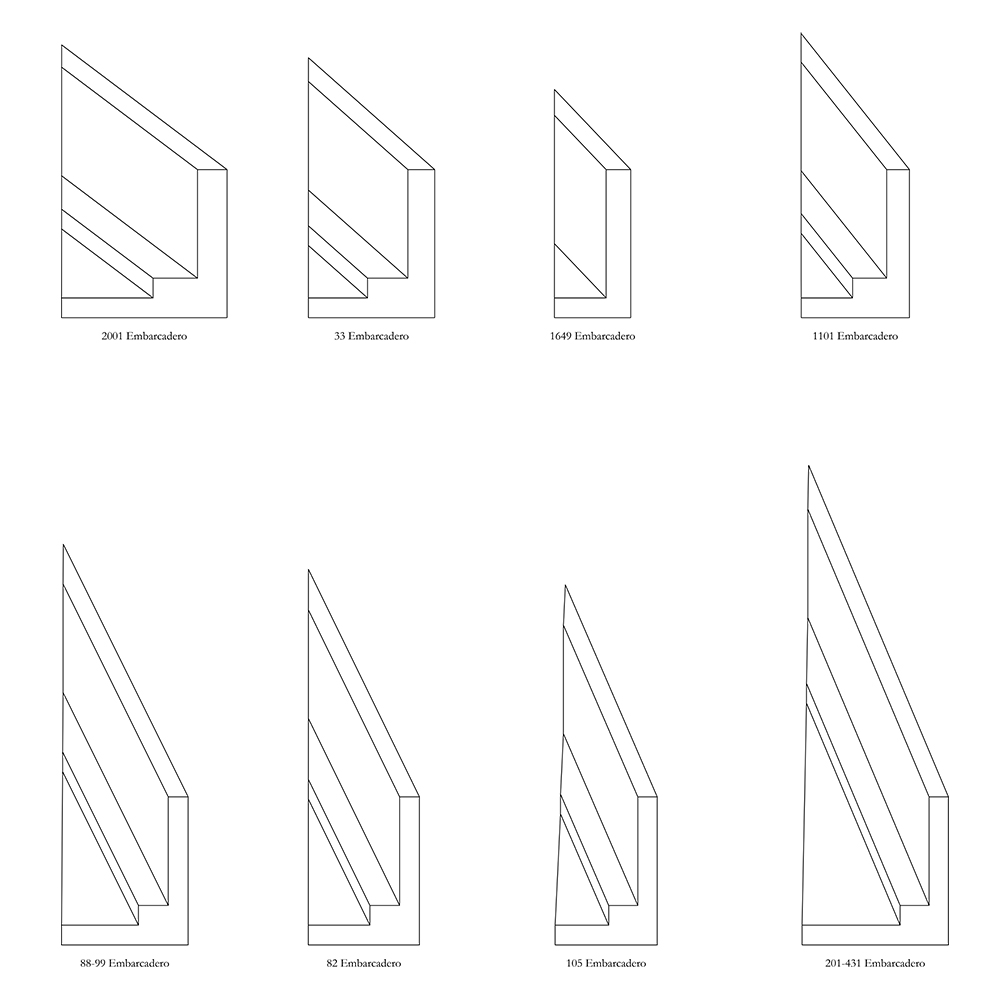

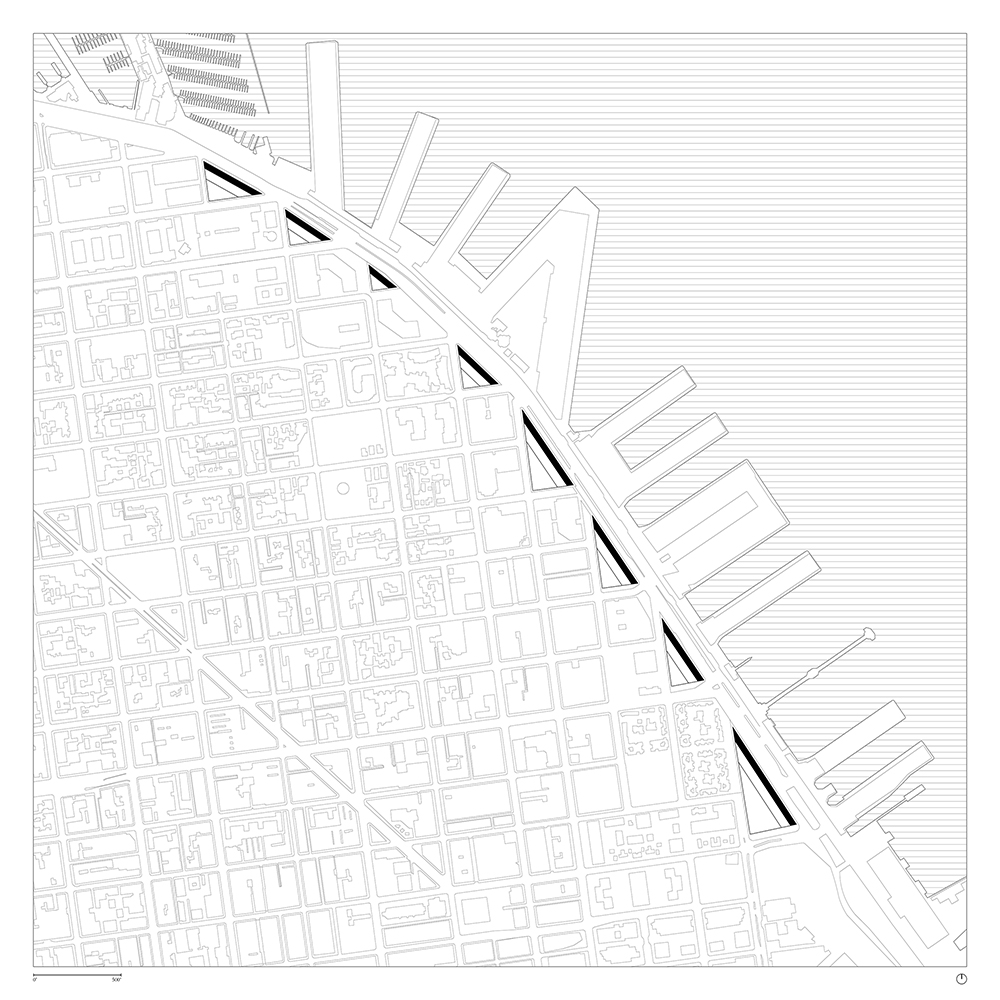

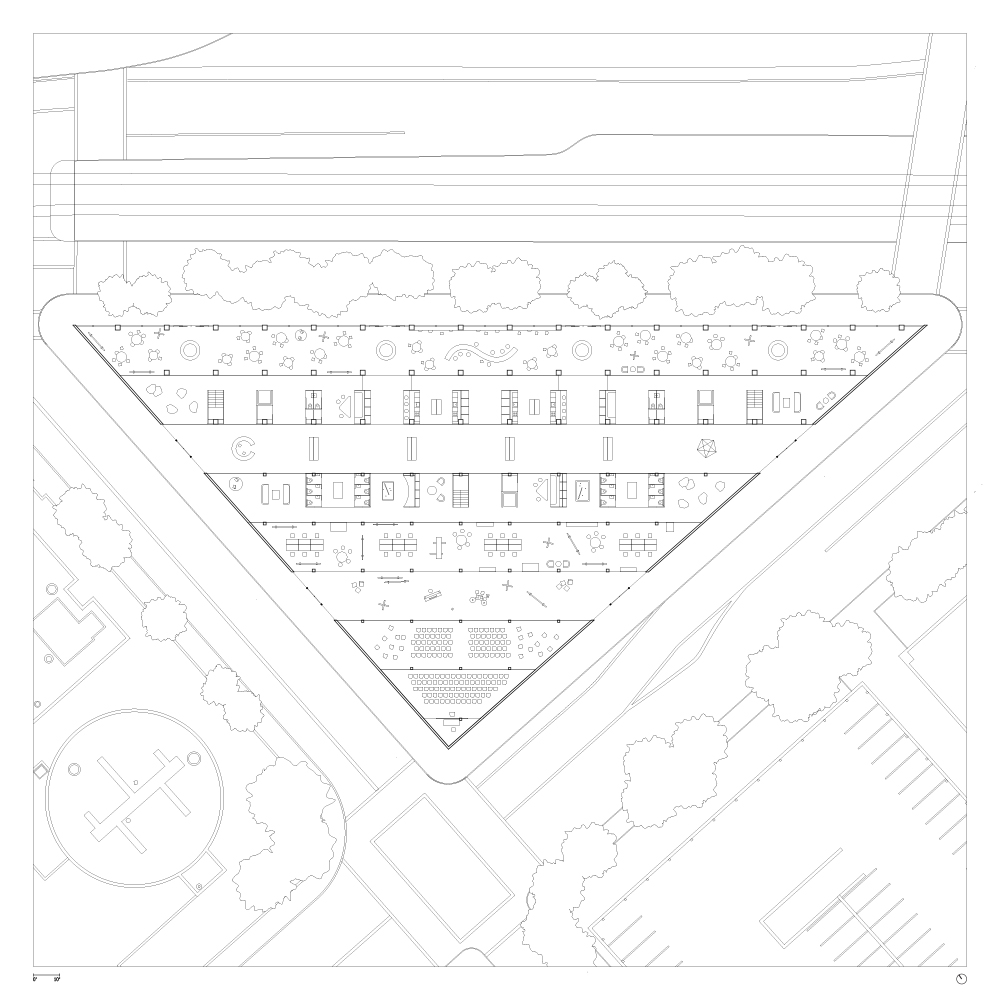

The project takes advantage of the residual, often discarded triangular sites along the waterfront, three-quarters of which are currently used as parking lots. This is a common phenomenon when a city grid hits a sinuous boundary. Too often the sites that do not conform to the typical rectangular lot are left untouched. The project refutes the NIMBYist idea that building on the waterfront would block “the view.”

of the bay from Telegraph Hill, an idea predominantly proliferated by a small group of wealthy individuals who fear the devaluation of their properties as a result of increased density in the neighborhood. As recent as 2014, with the passing of the “Waterfront Height Limit Right to Vote Act,” the existing minimum building height limits cannot be increased unless it is approved by San Francisco voters.(2) Meanwhile, San Francisco is experiencing a dreadful housing crisis exemplified by a scarcity of affordable housing in the city center. Positioning the project in the center of the city not only revives one of the historical advantages of the residential hotel, specifically the ability for dwellers to walk to work, but also gives a new visibility to a domestic typology whose urban presence has been increasingly suppressed and concealed over the past 60 years.

As a result, the project envisions an SRO 2.0 which could accommodate mid-life singles (for lack of a better word). Whether it is due to the decision to abstain from marriage, the result of a divorce, or the unexpected death of a spouse or partner, many middle-aged individuals are finding themselves confronted with life as a single. As a result, singles have quietly emerged as a dominant demographic across the United States. Despite this increase, the financial and social implications of living outside of the nuclear family are quite profound and the difficulties only compound with age. There is a certain acceptance of single life throughout ones twenties and even thirties, after which point the expectation is to marry, settle down, and have children. Yet despite the prevalence of such situations, the topic remains relatively taboo; an inconvenient reminder that the American Dream is not without its flaws. Without the financial and legal bene ts provided to married couples, midlife singles are an especially vulnerable subgroup in a marriage-centric society.

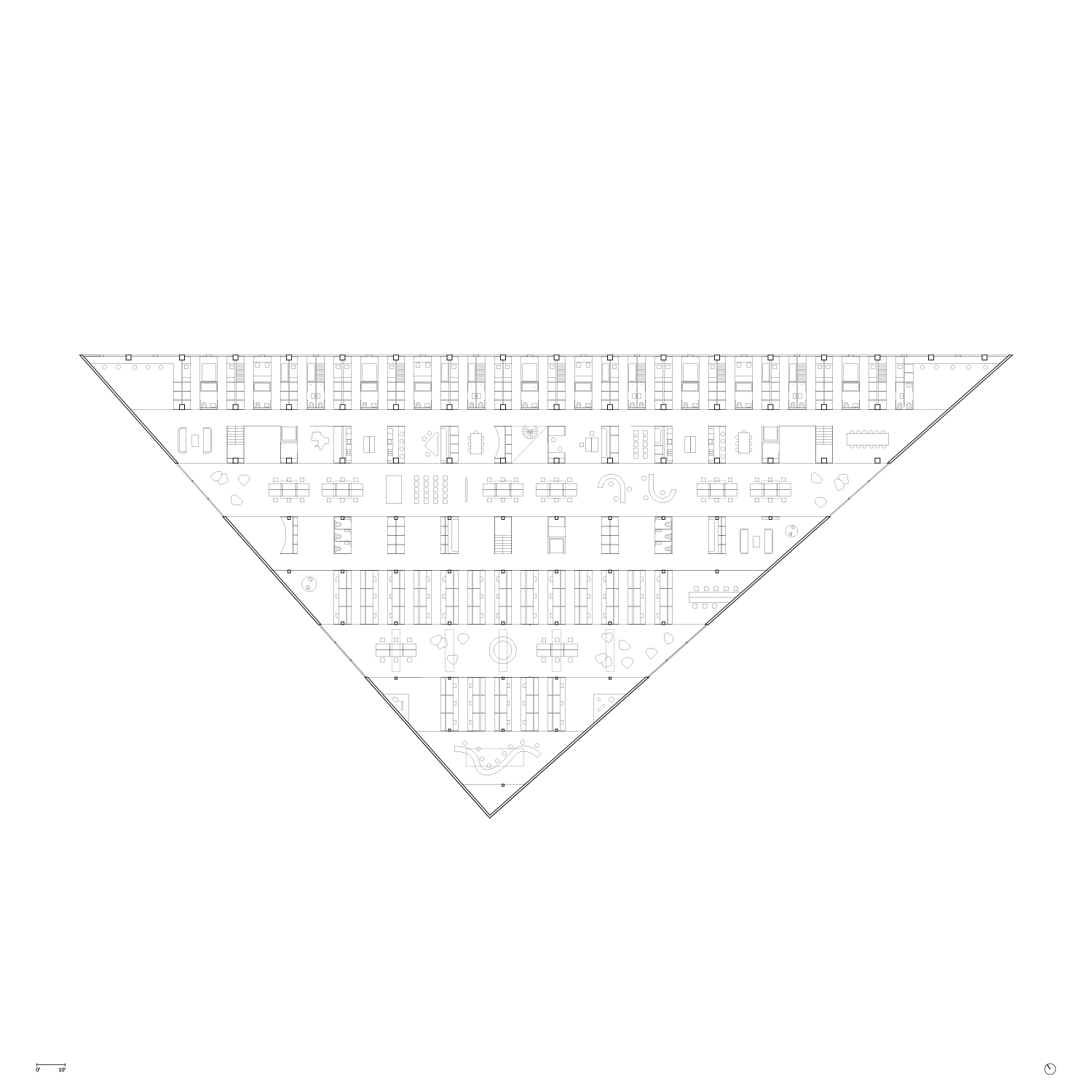

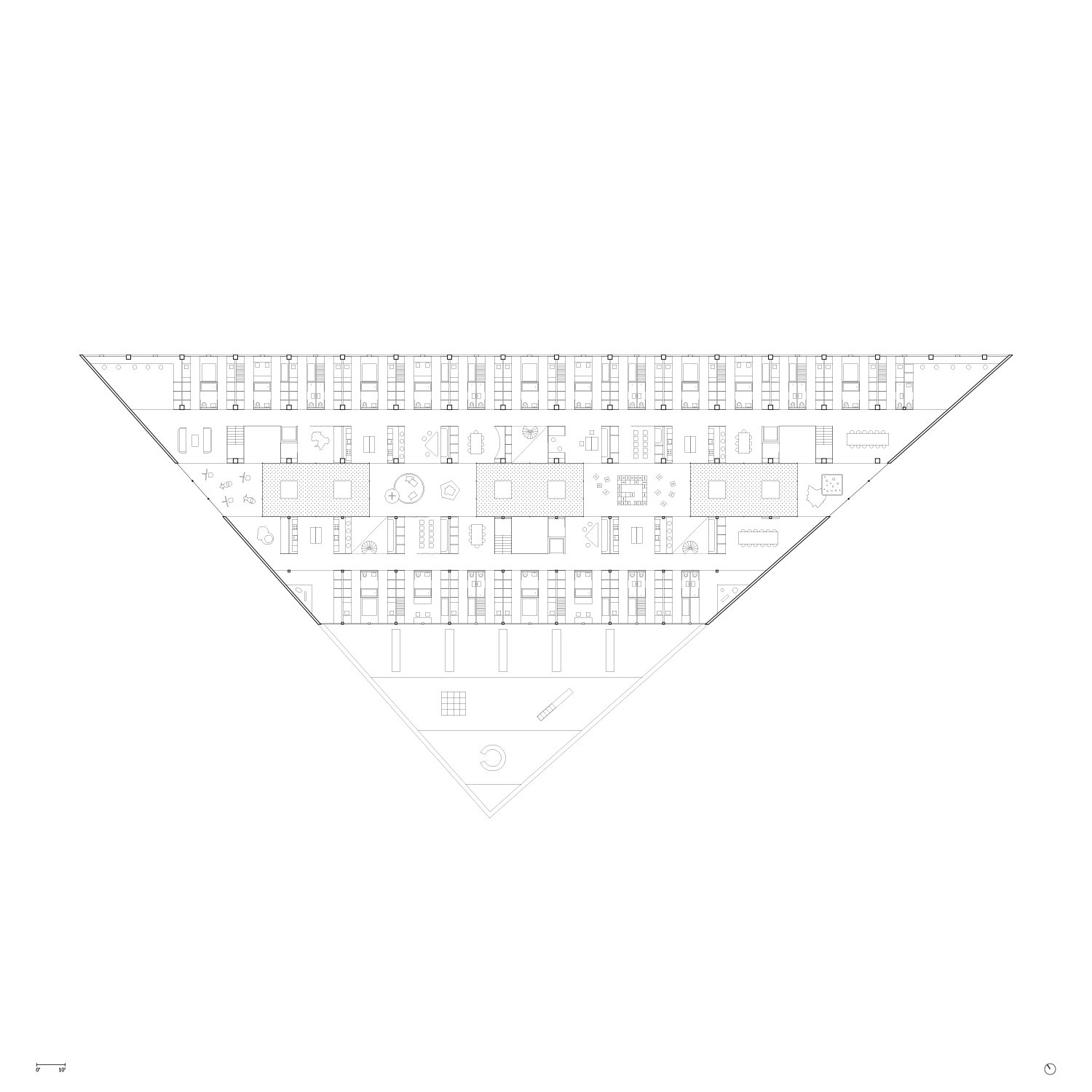

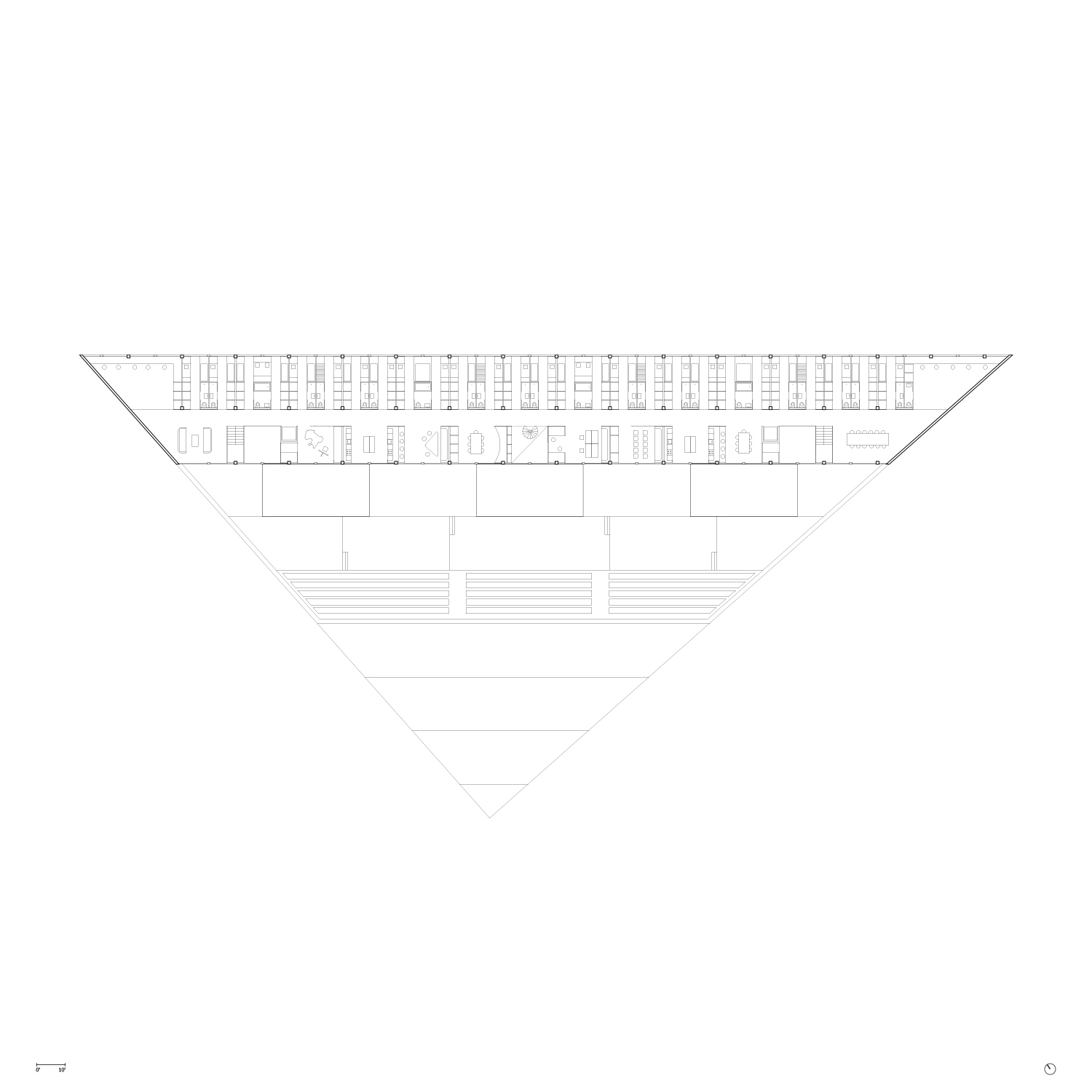

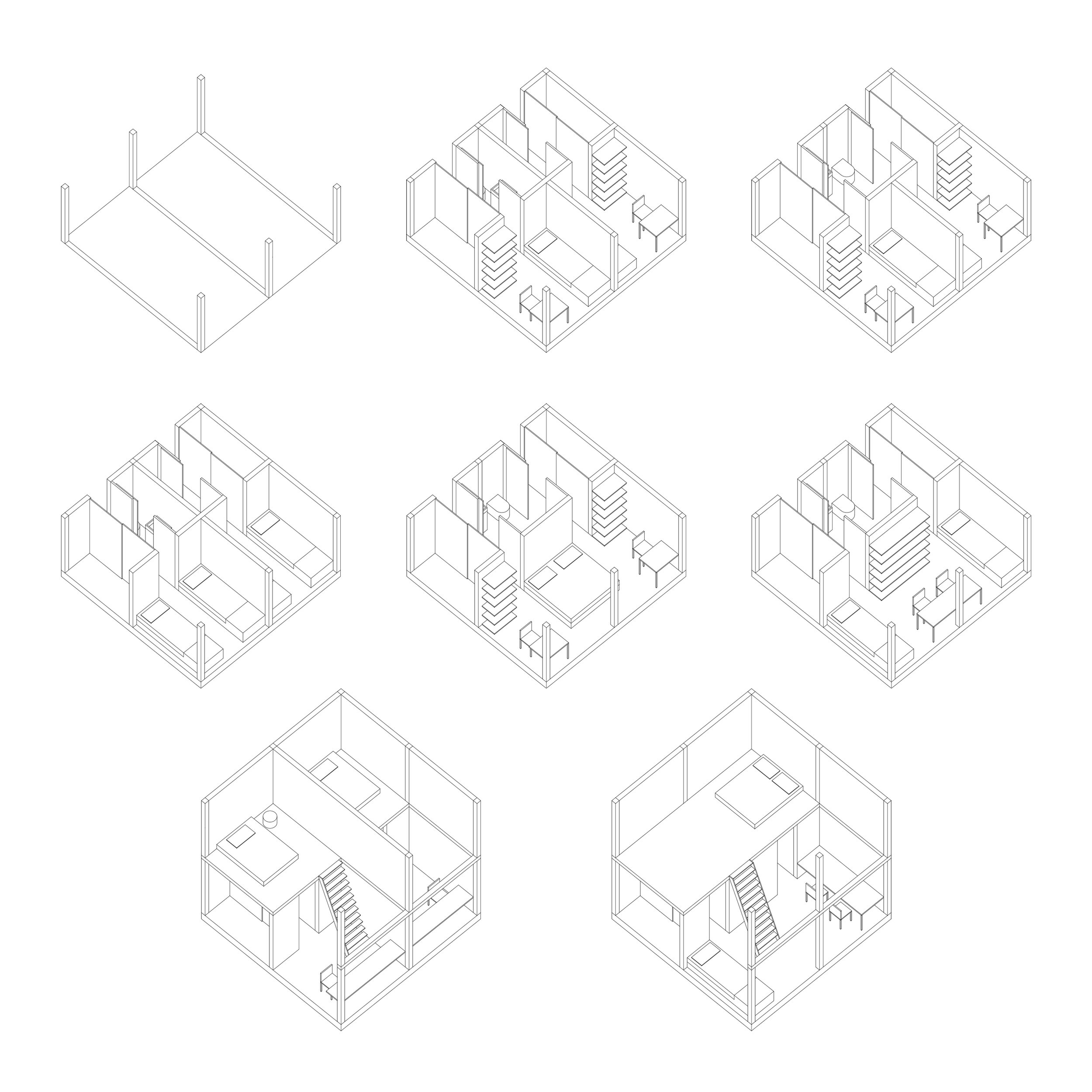

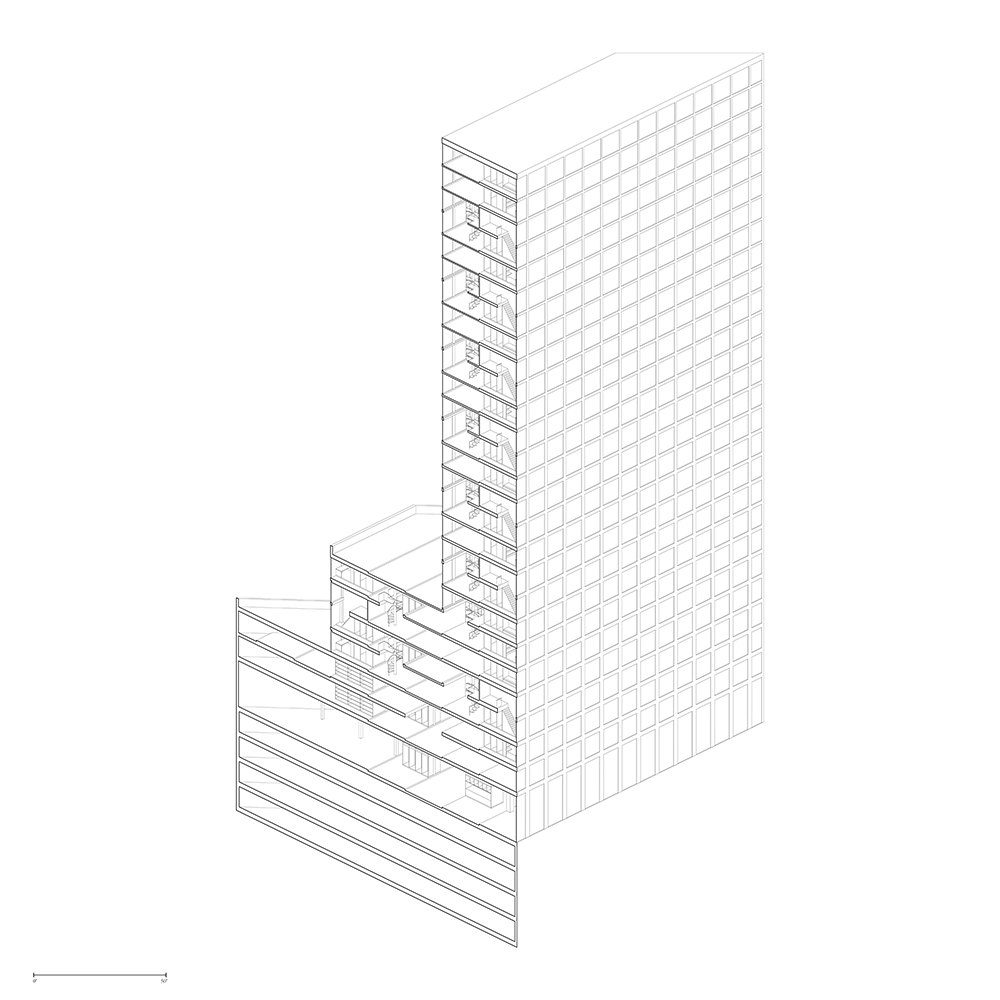

Dividing the parcels into equal strips was a pragmatic answer to the problem that arose from having to work with eight different triangular sites. The columnar grid defines the elementary structural framework of the building in between which cabinetry gets inserted to further organize spaces. The north-east strips of the towers host the private units and face the water while the south-west strips host the shared spaces facing the city. The plywood cabinetry becomes an apparatus to contain all functions related to domestic labor: resting, cooking, storing and cleaning. By concentrating the reproductive functions in the static cabinetry, the framed spaces can respond to dynamic changes that defines our lives. The cabinets are arrayed along the strips in a progressive rhythm in order to create a gradient of privacy. In Ritm v Arkhitekture, Ginzburg argues that geometric forms can always be interpreted as “static rhythm”, finding its most powerful manifestation in the poetic “rhythm of repetition.”(3) The rhythmic structure established by the cabinetry not only suggests one’s movement or procession through the space, but also a social organization emerging through ritual or habitus.

The primary module at work is a pair of units with a shared cabinet in the middle. As non-structural elements, the cabinets can easily be altered to merge or subdivide units. Unless the unit is combined to accommodate a larger group of people, the cabinets are always shared. Inserted within four columns, the units can remain separated or be combined in order to accommodate a larger group of people, such as a couple, family, or a group of single individuals. Like the pews of Michelangelo’s Laurentian Library, the cabinet is integrated into the structure of the building and ultimately replaces the wall; furniture becomes a primary architectural element.

Too often, single individuals live communally up until the moment where they want to have kids, thereafter feeling obligated to find more traditional domestic accommodations primarily because the spaces in which they live lack the ability to easily adapt or expand to support such a transition. Groth explains that “[i]n another departure from the typical household culture of the United States, residents of hotels keep themselves freer of material possessions than their suburban counterparts.”(4) In this lineage, the goal is to reinvent a space where the dweller is freed from the anxiety of constant possession as all necessary furniture is provided.

The eight towers are envisioned as “social condensers,” referencing the use of pro- grams in the well-known experiments on communal living in the 1920’s by Russian Constructivist. Living together can only be attainable if there is a shared ethos be- tween the dwellers. Therefore the larger programs are imagined as social catalysts. By reducing the size of the individual units, larger shared spaces are provided. The kitchen, living rooms and un-programmed rooms are directly adjacent to the units, and repeated from floor to floor. From the fourth to the eight floor, the tower gets thicker to insert program such as childcare and playgrounds to better accommodate dwellers with children. The larger shared programs such as the gym, library, swimming pool, steam rooms, auditorium, mini-golf course and workshops happen on the first and second floor and are shared across the different buildings. These pro- grams, more than mere spectacles, are envisioned as places of leisure and relaxation that could create a sense of social unity within the community. Each tower has a specific program that is determined by both the size of its lots and a careful analysis of its surrounding context.

The city has been willing to develop this part of the bay area but has found resistance from lobbyists. Through the revitalization of a more communal form of the SRO and residential hotel typology, new housing stock can emerge to accommodate those individuals that are often neglected or altogether forgotten as San Francisco’s housing market increasingly shifts its focus to the predominantly young professionals of the tech industry.

Spring 2016 // Critic: Pier Vittorio Aureli with Emily AbruzzoIn Collaboration with Dorian BoothProject published in Retrospecta 39San Francisco, California

(1) Paul Groth, Living Downtown: the history of Residential Hotels in the United States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 1

(2) “Waterfront height Limit Right to Vote Act,” Department of Voting and Records, City of San Francisco, June 2014.”

(3) Anya Bokov, “Rhythm and Other Elements: Analysis and Composition in Soviet Avant-Garde Architecture” in Analytic Models in Architecture by Emmanuel Petit (New Haven: Yale SOA, 2015), 20

(4) Paul Groth, Living Downtown: the history of Residential Hotels in the United States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 8